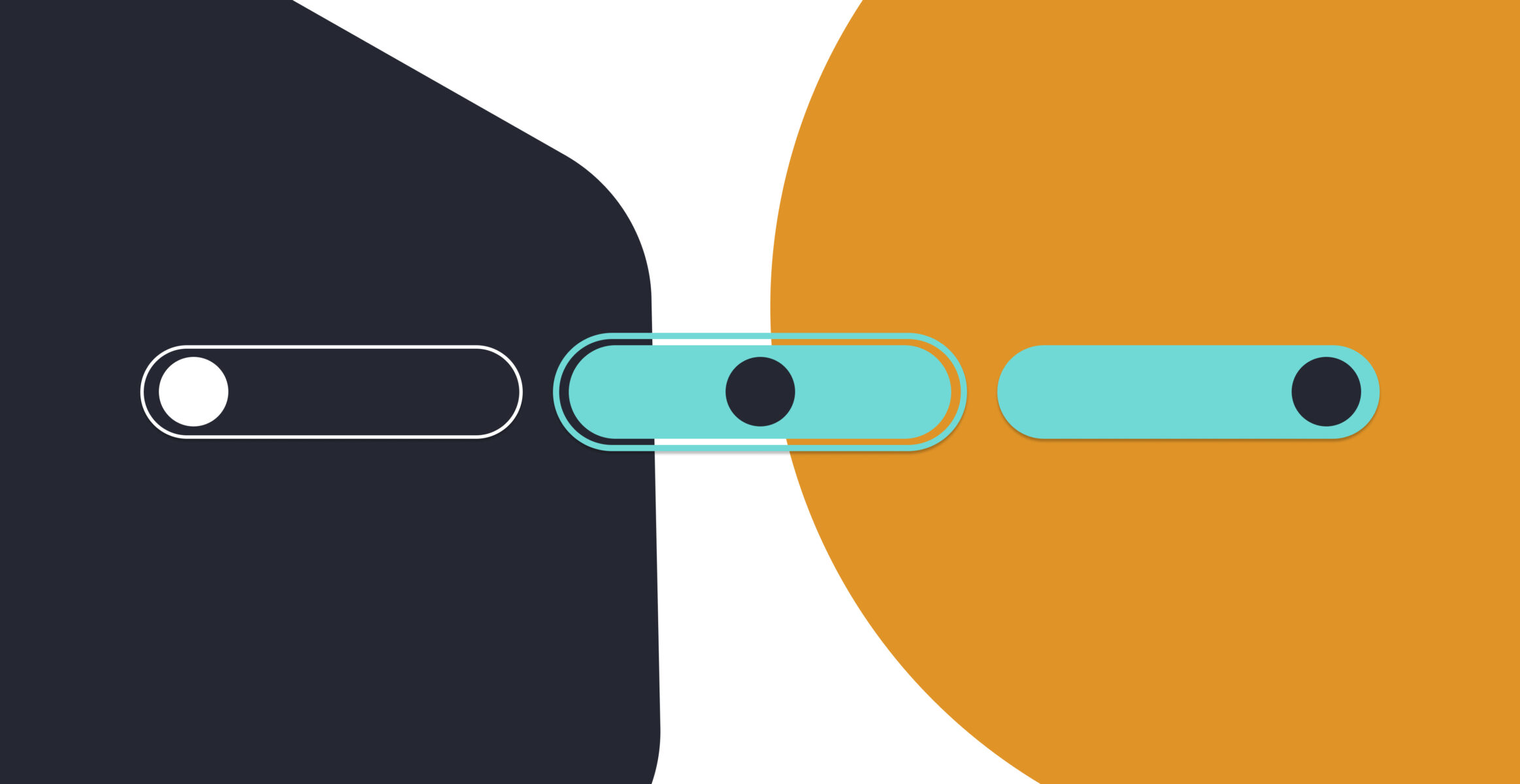

Stop for a minute and think about something that you were able to use without any explanation. I’m not talking about just digital products, I mean anything. When you were a little kid and the other children were playing with a hose in the backyard, it came with no instructions. You picked it up, and you were in control. The feeling was exhilarating. When you grew a little older and you were learning how to ride a bike, you had to learn the skill, but no one needs to show you HOW to operate it. The seat is obviously where you sit, the pedals’ location and motion clearly indicate their function. The same is true for the handlebars. You had to learn how to balance it, but you knew exactly how to use it. There’s a term for this. It’s called “affordance.”

When a new invention is born into the world that combines essential functions with the right amount of affordance, it can change the world. The aforementioned bicycle changed the world. Carlton Reid, in his book “Roads Were Not Built for Cars,” points out that they were the first mass-produced personal transportation vehicle, and their mass adoption required better roads, which in turn literally paved the way for the automotive industry. Many of the innovators of the Industrial Revolution would begin their mechanical fascination by working on bicycles, including the Wright brothers.

Looking more recently, many of us are old enough to remember all of the innovations of personal computing, but perhaps none were quite so impactful on our everyday lives as the invention of the smartphone. I would submit that the device’s affordances deserve much of the credit for this. Before smartphones, computers required some level of explanation to understand how to interact with them, but with the smartphone, so much of the interaction was exactly what you would expect to do. Is the text too small? Pinch to zoom in. Want to go to the next page? Swipe from right to left. People often joke about how little children seem to be able to use smartphones and iPads before they can talk. That’s actually a sign of an incredible level of affordance. It’s instinctual.

Intuitive Design Requires Vision

It’s about more than just anticipating what people like and will use. It’s considering the possibilities no one has even thought of yet. More design vision is required to tap into what will be popular beyond six months or a year from now. Take our previous example of the smartphone. The creation of the iPhone was a major departure from what was currently trending in phone technologies. Until that point, cell phone designers were creating many disparate designs, each focused on the needs of a certain user type. Do you like photography? This is the phone for you! Do you like music? Try this phone. Send a lot of email? Well, guess what… The inventors of the iPhone realized that if they could just create a phone that was great for multiple things, then EVERYONE would want one. It’s actually in Steve Jobs’s immortal product rollout, “A phone, a music player, and a web browser… Three new devices.” The initial vision was only the start. I don’t think even the initial designers could have imagined all of the needs their initial smartphone design would be fulfilling almost 20 years later.

Knowing Your User Is Essential

While few of us in the tech industry get to design products for audiences as broad as iPhones, we all need to understand exactly who we’re building for. Creating effective, intuitive products starts with developing a deep understanding of the user, not just their needs in relation to the product, but also elements of their personality, habits, and environment that may influence how they interact with it.

When we create user personas, we ask targeted questions to uncover this context. For example, if we’re building logistics software for a shipping company, we need to consider everything from the type of device drivers we will use to whether it’s mounted on a dashboard, the drivers’ average age, and even how reliable the network connection is along their typical routes. Each of these details helps inform decisions that make the final product more intuitive, useful, and effective for the people who rely on it.

I remember the first time I watched Spike Jonze’s film Her. Joaquin Phoenix plays Theodore, a lonely man who falls in love with his AI personal assistant, Samantha, voiced by Scarlett Johansson. It’s a beautifully told story with exceptional acting, but what struck me most wasn’t the romance, it was how Theodore interacted with Samantha.

She wasn’t on a screen or behind an app interface. She existed in a small device, about the size of a deck of cards. He never tapped through menus or adjusted any settings; she was just there. Present. Effortless. Natural.

In the decade since that film’s release, I’ve watched technology move rapidly in that direction. Our interactions with digital products are becoming so seamless, so embedded in our daily lives, that soon we may barely realize anyone designed them at all.

And to some extent, no one will be designing them, not in the traditional sense. Instead, users will shape their own experiences in real time, dynamically, intuitively.

To some, that might sound like a bleak future for UX and design professionals. But I’m hopeful.

I believe the future will still belong to creative people. Those who can listen deeply, understand users even when they can’t articulate their needs, and express those needs in ways that are clear, elegant, and human. We may move beyond screens and wireframes, but the need for thoughtful, empathetic design will only grow.